Summary

Planning our time requires thinking ahead about how long tasks take and making decisions about prioritizing the ways we spend our time. Students have some experience doing this daily, but in their college and career lives, they will be expected to estimate and balance their own time more and more to achieve their goals.

Essential Questions

Are we aware of how we are spending our time?

Do we spend our time in ways that are valuable to our life goals?

Snapshot

Engage

Explore

Explain

Extend

Evaluate

Materials List

Activity Slides (attached)

Stopwatch (optional)

Materials for your choice of Minute to Win It games

It Takes as Long as It Takes handout (attached; one per student)

Time Log handout (attached; one per student)

Time Spent Pie Chart Template (attached; one per student)

Wheel of Time Handout (attached; one per student)

Learning Goals

Estimate with accuracy how long everyday tasks take to complete.

Prioritize how to spend time to achieve desired outcomes.

Engage

10 Minute(s)

Display slides 3-4 and share the Essential Questions and Learning Objectives for this activity. Often students may not think about how long a task will take and end up pressed for time, rushing to get things done.

Move to slide 5 and explain to students that Minute to Win It is a game that challenges them to complete a task in less than a minute. Choose one or more of the following games and give as many students as possible a chance to compete so they can reflect on what happens when we feel rushed.

Face Cookie: Provide each student with a cookie (Oreo size is best). Each student places the cookie on their forehead. They need to move the cookie to their mouth using only their face muscles before time is up.

Balloon Juggle: Give each player 3 balloons. They work alone to keep all of the balloons in the air for a minute.

Cabbage Roll: Using just their nose, roll a cabbage from a starting line to a finish line across the room in under a minute.

Use the timer on slide 6 to start and end each round.

After students have had a chance to compete, move to slide 7 and ask the group the following questions:

How does time pressure affect your performance?

Did some tasks take longer or less time than you thought?

Were there unexpected challenges to the task that made it harder?

Explain that in the next few activities students will consider how long tasks take in an effort to get better at planning ahead so that they don’t have to feel that everything they do in life is a Minute to Win it Challenge. Instead, they can have time to think and plan to see better results.

Explore

5 Minute(s)

It can be surprising how long it takes to complete a task. Just like with the Minute to Win It Challenges, things that seem simple can end up being much more complicated and taking more time. With this task, students think about how long things take to complete that are part of their regular routines. Display slide 8. Hand out the It Takes as Long as It Takes chart to each student. Have them predict how long they think it takes to complete each of the everyday tasks listed in the chart.

Remind students we can’t really live our lives at a constant fast pace as if we are constantly competing in a Minute to Win It challenge, so they shouldn’t view it as recording their "best time" but how long they think things usually take.

Have students take their charts home and record how long it actually takes them to do these tasks. Have them return with a completed chart in the next session.

Explain

10 Minute(s)

After students have had time to record their time, discuss how long tasks actually took compared to their estimates. Display slide 9 and ask:

Did some things take longer than you thought? Less time?

How did it feel to finish more quickly than you thought, or did it actually take longer?

Explain that now since they are experts on how long it takes to do what they have to do, how about the unexpected things? Show slide 10 and introduce the Time Log handout.

Ask students to record what they did and how long they did it - note in the category column if it was fun, school, work, etc.

Extend

15 Minute(s)

Display slide 11. Have students look over their time logs and add up the times for each category they have identified. They can use the Time Category Totals table on page 2 of their time log to record this information.

After students have recorded their totals, have them create a pie chart. They can paste their totals into a Google Sheet and follow the instructions in this video on slide 12: "Create a Pie Chart in Google Sheets."

They can follow the instructions on slides 13-17 to insert a pie chart into their document and update the information using their Category Totals table.

After students have successfully created a pie chart, move to slide 18 and provide them with time to reflect and discuss the following questions:

Do you feel your pie chart represents how you spend your time?

Are there things about how you spend your time that you would like to change?

Are there things you ought to change to manage your time better?

Evaluate

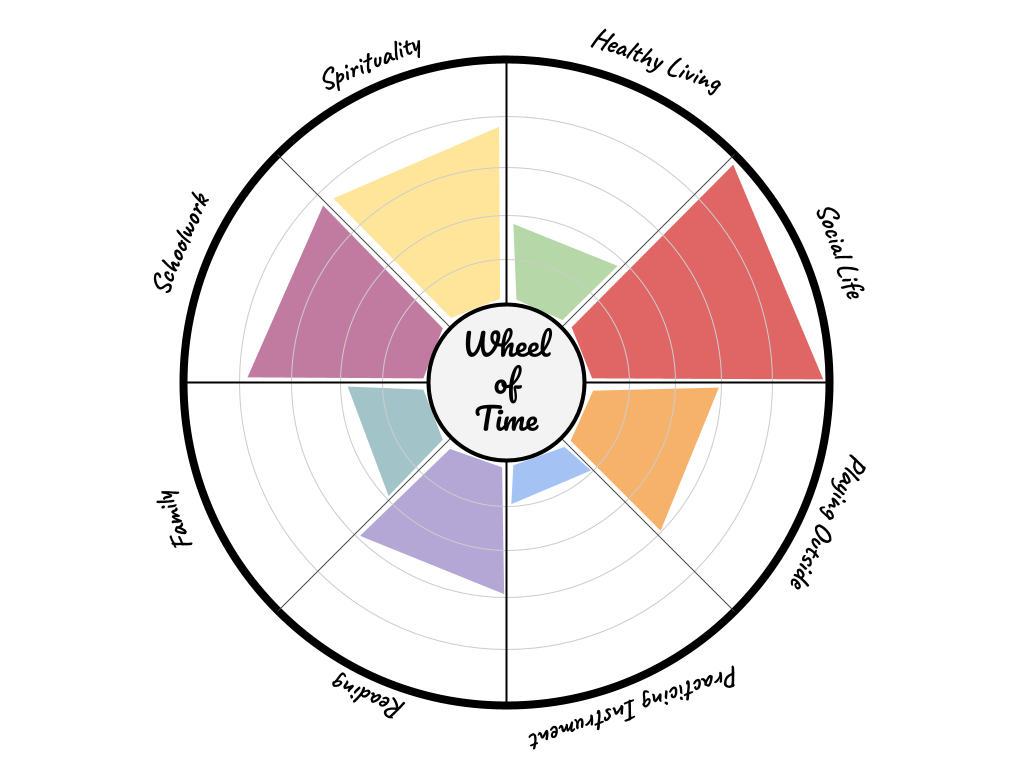

Move to slide 19. Have students reflect on their satisfaction with how they spend their time by creating a Wheel of Time chart.

Have students follow the steps below to create their Wheel of Time chart:

Have them choose 4–12 categories that reflect how they want to spend their time.

Ask them to consider what kinds of time they need to reach their personal goals in life.

Advise them that these may not be the same ones they used to label how they currently spend their time.

Inform them that this is the time to consider whether there are some categories they would like to spend their time that aren’t represented in how they currently use their time.

Ask them to label the Wheel of Time sections for the categories they have chosen.

When they have completed their selections, invite them to spend some time reflecting on how they currently spend their time in each of these areas.

Instruct them to score each category 0–5 based on whether they feel they are giving enough time to this area.

Have them shade in that section up to the line 0–5 based on the score each student has given that area.

Ask them to reflect on this activity:

Does their time use have a balance between work and play?

Does their time use align with what they want to accomplish?

Display slide 20. Have them choose one area that they feel they are neglecting and write a goal for how they will spend more time on that area in the coming week.

Ask them to revisit and recolor a Wheel of Time every week or two so they can continue to reflect on whether they are balancing their time according to their needs and goals. It’s more important to balance their time than to have a perfect score in each category.

Follow-Up Activities

Consider following up this activity with "I Didn’t See That Coming: Task Management 101." In this activity, students learn how to use calendars to stay on track and to avoid roadblocks that keep us from achieving our goals.

You may also follow up with the activity "Break It Down." In this activity, students learn how to add micro-goals to their calendars to stay on track.

Research Rationale

Regardless of the focus of the extracurricular activity, club participation can lead to higher grades (Durlak et al., 2010; Fredricks & Eccles, 2006; Kronholz, 2012), and additional benefits are possible when these clubs explore specific curricular frameworks. Club participation enables students to acquire and practice skills beyond a purely academic focus. It also affords them opportunities to develop skills such as self-regulation, collaboration, problem-solving, and critical thinking (Allen et al., 2019). When structured with a strong curricular focus, high school clubs can enable participants to build the critical social skills and "21st-century skills" that better position them for success in college and the workforce (Allen et al., 2019; Durlak et al., 2010; Hurd & Deutsch, 2017). Supportive relationships between teachers and students can be instrumental in developing a student’s sense of belonging (Pendergast et al., 2018; Wallace et al., 2012). These support systems enable high-need, high-opportunity youth to establish social capital through emotional support, connection to valuable information resources, and mentorship in a club context (Solberg et al., 2021). Through a carefully designed curriculum that can be implemented within the traditional club structure, students stand to benefit significantly as they develop critical soft skills.

Resources

Allen, P. J., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Little, T. D., & Noam, G. G. (2019). From quality to outcomes: A national study of afterschool STEM programming. International Journal of STEM Education, 6(1), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-019-0191-2

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., & Pachan, M. (2010). A meta-analysis of after-school programs that seek to promote personal and social skills in children and adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3-4), 294–309.

Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2006). Is extracurricular participation associated with beneficial outcomes? Concurrent and longitudinal relations. Developmental Psychology, 42(4), 698–713. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.ou.edu/10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.698

Hurd, N., & Deutsch, N. (2017). SEL-focused after-school programs. The Future of Children, 27(1), 95–115. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44219023

Kronholz, J. (2012). Academic value of non-academics: The case for keeping extracurriculars. Education Digest, 77(8), 4-10.

Pendergast, D., Allen, J., McGregor, G., & Ronksley-Pavia, M. (2018). Engaging marginalized, "at-risk" middle-level students: A focus on the importance of a sense of belonging at school. Education Sciences, 8(3), 138.

Solberg, V. S., Park, C. M., & Marsay, G. (2021). Designing quality programs that promote hope, purpose, and future readiness among high need, high risk youth: Recommendations for shifting perspective and practice. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720938646

Vigil, Britni. (2022). 200+ Minute to win it. Games for groups. Play party plan. https://www.playpartyplan.com/minute-to-win-it-games-for-groups/

Wallace, T. L., Ye, F., McHugh, R., & Chhuon, V. (2012). The Development of an adolescent perception of being known measure. The High School Journal, 95(4), 19–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23275415